Pixar did not start out intending to make films. The company was founded back in the late 1970s as part of Lucasfilm, as a division called The Graphics Group, dedicated to exploring just how the still relatively new computers might be used to improve films. This, oh readers, was back not just in the days of floppy discs and the days when 1 meg of ram for a home computer was completely unheard of, but also things like punch cards and early DOS and….you know, just thinking about this is depressing. Let’s just say that although computers had potential—something George Lucas was among the first to recognize—they had a long way to go before they could transform films all that much—something George Lucas was a little less willing to recognize.

But even Lucas could recognize the limitations of computer technology at the time. Instead of trying to have his computer experts create the entire film, he sent them to work with one of the Lucasfilm subsidiaries: Industrial Light and Magic. A subsidiary initially founded to help create the special effects sequences in Star Wars (1977), Industrial Light and Magic soon found itself juggling numerous projects from other film studios impressed by their digital effects and rendering work, and trying to find ways both to improve on this work and—a biggie—save money while doing so.

The result of all this was a short, computer generated sequence in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan (1982), a “blink and you’ll miss it moment” that managed to show the potential of computerized imagery—and suggest the possibility of creating an entire film with only computers. But before anyone could get too excited about this, the computer group found itself with a new problem: George Lucas, their boss, was in the middle of his very expensive 1983 divorce proceedings, and needed to sell off assets, quickly.

The Graphics Group was one such asset. But, well aware that even the most optimistic person in Hollywood might not be willing to back a company that specialized in then-nonexistent full length computer animated films while creating hardware on the side, the group’s members reformed themselves into a hardware company that made short computer animated sequences on the side. The hardware was enough to attract the attention of recently fired and looking for something to do Steve Jobs; the computer animated sequences and rendering software were enough to raise the interest of multiple Hollywood studios and Disney, still looking for a cheaper way to color and ink animation cells, decades after The 101 Dalmatians. The cash from Steve Jobs was enough to allow The Graphics Group to be spun off into an independent company called Pixar—and to let George Lucas pay off at least part of his divorce settlement.

As it turned out, in an unexpected twist, the main company product, hardware, continually lost money, while the sideline, computer animation, kept bringing in—well, not money, exactly, but positive attention. Most of this was thanks to John Lasseter, a man who had been fired by Disney in the early 1980s for having what was called an “obsession” with computer animation—a word that soon proved to be all too weak. Lasseter found himself wandering over to Lucasfilm and The Graphics Group, where he continued to work on computer animated sequences, developing fully computer animated cartoon shorts and some ads.

Buy the Book

The House in the Cerulean Sea

Eventually, this work caught the attention of Jeffrey Katzenberg, then chairman of Walt Disney Studios. Katzenberg had already been developing a relationship with Pixar, who was providing the hardware and technical consulting for Disney’s CAPS system (a computerized method of saving money on inking and coloring animation cels, as well as allowing animated films to mimic swooping camera angles), and also liked Lasseter’s little cartoons. By 1991—as Katzenberg looked at the final renderings for Beauty and the Beast and some of the initial work on The Lion King and Aladdin, he signed a $26 million deal with Pixar to do the then unheard of: produce not one, but three computer animated films, which would be released by Disney and its distribution arm, Buena Vista. It was a then-rare case of Disney releasing a film that was not produced by its own studio (although Tim Burton worked out a similar deal for The Nightmare Before Christmas), with all sides agreeing that what would become Toy Story would be credited as “Walt Disney Presents a Pixar Production.”

It was a desperately needed financial shot in the arm for Pixar, still relying heavily on Steve Jobs’ infusions of cash, and also an opportunity for John Lasseter to work with Disney again—if this time on slightly better terms. It was also an excellent deal for Disney, allowing the company to continue to position itself as an animation leader while keeping most of the profits and the characters—a deal that would later lead to the creation of one of Disney’s most profitable franchises. It was also the start of something marvelous: the Pixar films.

Which brings me to Toy Story.

As eager as Katzenberg was to work with Pixar and John Lasseter, his response to Pixar’s first pitch—a tale where ventriloquist dummy Woody was a MEAN TOY—was his by now standard response of HELL NO. Instead, Katzenberg wanted a humorous mismatched buddy picture. Pixar and Disney animators went back to the drawing board, slowly creating the characters of pull toy Woody, a cowboy, and action figure Buzz Lightyear, named for astronaut Buzz Aldrin. (If you watch very carefully, you can see some of the original concept art for Woody and Buzz stuck on the walls of Andy’s room.) And they found their inspiration: Buzz, unlike most of the other toys in the story, would not realize that he was a toy.

The brainstorming sessions, however, did not exactly solve all of the story’s problems. Indeed, Disney was so unimpressed with the first half of the film—a half that still featured Woody as a Very Mean Toy—that Disney executive Peter Schneider ordered a production shutdown. The Pixar writers—with some help from Joss Whedon, who spent two weeks tinkering with the script and added a dinosaur—took yet another stab at the script. Finally, in February 1994—three years after Pixar had first pitched their ideas for Toy Story—the script had reached a point where everyone was more or less happy, allowing production to continue. Pixar more than tripled its animation production staff, somewhat to the horror of Steve Jobs (still Pixar’s major backer, even after the Disney contract) and plunged ahead.

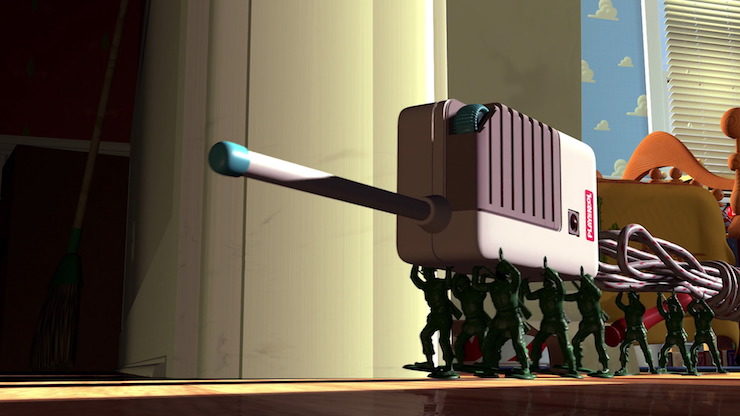

Even then, the script still needed more tinkering. The filmmakers, for instance, were not allowed to use all of the toys they wanted to feature, with Mattel flatly refusing to license Barbie for an experimental computer film, and Hasbro unhappy with a plot that would feature a character blowing up their beloved (and lucrative) G.I. Joe action figures. Toy Story settled for the small plastic army figures instead—figures which Burger King later ruthlessly stripped of weapons in their later cross-promotional deal, and which could be happily blown up without upsetting Hasbro. Meanwhile, Barbie had to be swiftly erased from the script.

Music was another huge tangle. Lasseter and the other Toy Story writers and storyboard artists did not want the toys to suddenly stop and sing, and also argued that, as a buddy movie about one toy unaware of his true nature, and a second toy unable to express his real fears, the musical format would not fit. Disney, flushed from the success of The Little Mermaid and, as production developed, Beauty and the Beast, and eyeing all of the potential marketing opportunities that songs like “Be Our Guest” offered, wanted a musical, and also, very much wanted a song that could be released as a Top 40 hit. In the end, the companies compromised by hiring Randy Newman to write songs that could be sung, not by the characters, but as background music to some scenes and over the credits.

Randy Newman came up with Toy Story’s signature song, “You’ve Got a Friend in Me,” played during the opening sequence and the closing credits. Despite technically not exactly being a Disney song, at least not at first, and despite inexplicably losing the Oscar for Best Song to “Colors of the Wind,” from Pocahontas (really, Academy?), the rollicking number is frequently listed among Disney’s best, and Pixar continues to use it in a number of Toy Story related projects.

Beyond all this, Pixar struggled with the sheer technical complexity of creating the world’s first full length computer animated film—with less than 1/5 of the staff Disney had working on The Lion King—a film that, moreover, could illustrate all of the new possibilities offered by computer animation. To do this, Pixar more or less had to invent and code entirely new programming, including software that could move the characters through multiple poses, and new rendering techniques to ensure that the shadows and colors were more or less correct. Here, traditional animation set the example: as with traditionally animated films, Pixar assigned separate teams to handle separate elements of each frame, with some artists and programmers working on backgrounds, as others teamed up to work on individual characters, camera angles, rendering and special effects. Pixar also found itself adding and deleting scenes as the script continued to go through rewrites, adding to the production costs.

If music and technical issues were a tangle, with voice acting, Pixar struck gold. Nearly every performance, right down to the Little Green Men, is nearly pitch perfect, with Tim Allen infusing real joy into his performance as Buzz Lightyear, and Tom Hanks shifting effortlessly between that suck-up boss that insists that everyone follow the rules and keep going to these boring meetings, to a toy terrified of losing his position as a Favorite Toy, to complete exasperation at Buzz Lightyear’s ongoing inability to accept reality. The minor characters, too, are solid, particularly Wallace Shawn’s neurotic dinosaur and Don Rickles’ caustic Mr. Potato Head.

The voice acting is a major part of why, more than twenty years later, Toy Story still holds up well, even against the very latest computer animated features. Oh, not everything looks good—Pixar’s initial attempt to make realistic computer animated humans fails on a number of levels, with Andy’s hands looking particularly creepy. Notably, a few films after this, Pixar would largely abandon its attempt to make its computer animated humans look realistic, instead choosing to give the humans a more cartoonish look—a decision with the unexpected consequence of making the humans look more realistic and less creepy than they do in Toy Story.

To be fair, that creepy look does service both the plot and tone of the film, which has a rather dark undertone for a children’s film supposedly about anthropomorphic toys. In our first view of the toys, after all, they’re coming in for some rather harsh treatment from their kids, bounced harshly on the floor, thrown wildly into the air and even—GASP—LEFT IN A CRIB FOR A TODDLER TO CHEW ON.

(Mr. Potato Head would like to take this time to remind you that his packaging clearly says “AGES THREE AND UP.” I would like to take this time to remind Mr. Potato Head and all readers that toys labeled “AGES THREE AND UP” were clearly designed to be thrown directly at the heads of younger siblings who won’t shut up, no matter what more sober, responsible adults may tell you, and therefore could very easily end up in the mouth of a younger sibling, and that the true tragedy here is not what happened to either Mr. Potato Head or the younger sibling, but that, as a result of this, the older sibling will not get any ice cream which I think we can all agree is terribly unfair since she didn’t start it.)

So it’s probably not surprising that as much as Andy’s toys love Andy, they have a major tendency to panic at virtually everything, convinced that they are about to be forgotten in the upcoming move, or tossed away, or destroyed by Sid, the mean kid next door. They are all too aware that they are, in the end, just powerless toys.

With one exception: Buzz Lightyear, who, alas, does not realize he’s a toy. In this, he rather resembles my old dog, who did not realize he was a dog, a misapprehension that caused him quite a lot of issues in life. In Buzz Lightyear’s case, his very surroundings help reinforce his delusions: a few lucky landings on other toys and objects in Andy’s apartment allow him to “fly”—kinda. At least enough to earn wild applause from most of the toys (Woody points out that this was not exactly “flying”) and convince Buzz that yes, he can at least be airborne for a few minutes. It also helps that his internal backstory of a sudden crash on earth explains just why he’s having problems signaling his commanders to get a ride off the planet. And it helps that this creates some of the film’s most amusing and ridiculous moments.

Naturally, the delusion can’t last forever.

Equally naturally—spoiler—almost everything turns out ok.

The concept of toys that come to life whenever children leave the room was hardly new to Toy Story, of course (if memory serves, I first came across it in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1905 A Little Princess, and the idea wasn’t new to Burnett, either). But Toy Story does something special: it allows us to see exactly what the toys are doing while their owners are gone. As it turns out: playing, attending boring committee/neighborhood toy meetings (this is kinda awesome), and feeling terrified that at some point very soon they will be replaced.

It’s a message, I think, that speaks not only very clearly to many of the adults in its 1995 and later audience, but also to the animators and story developers who created it, many of whom had barely survived the Disney and Lucasfilm upheavals of the mid and late 1990s. As late as 1990, when Peter Schneider agreed to let Pixar create its first film outside the walls of the Disney Animation Studio, Disney only had two recent animation hits on their hands (Who Framed Roger Rabbit and The Little Mermaid) and the long term future of animation was in doubt. As was the long term future of Pixar and Disney, for that matter—Pixar continued to bleed money throughout the Toy Story production process, and although Disney CEO Michael Eisner was earning credit from Wall Street for turning the overall company around and had purchased the Muppets, Disney had only barely started its boom cycle of expanding its theme parks and cruise ships and purchasing additional media assets. (The then Disney/MGM Studios had opened in 1989, but Disneyland Paris would not open until 1992; Miramax and ABC would only be purchased in 1993 and 1995 respectively, and Disney Cruise Lines would not set sail until 1996.)

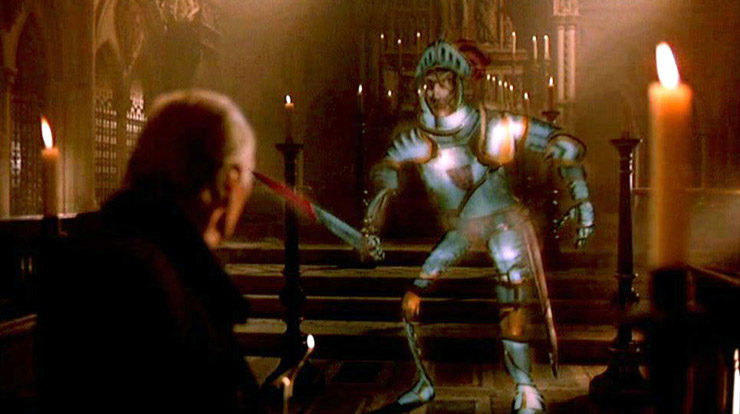

The story writers and the animators knew about change and replacement and getting left behind—accidentally or otherwise. The quasi-horror segment where Sid viciously “operates” on his toys, creating sad mangled misfit toys, can be and has been read as a metaphor for what the corporate life can do to creatives and creative work, and Pixar employees, like the toys they were creating, could also look through their windows—or, at least, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter—to see what could and did happen to the employees of other Hollywood conglomerates. Even the generally comfortable ending—Toy Story, after all, was aimed at children—has not one, but two dark underlying notes: Woody and Buzz need a literal rocket set on fire to stay as Andy’s toys, and it kinda looks as if the entire group of toys is about to be chewed up by a cute puppy.

The film’s second major plot, Buzz Lightyear’s slow acceptance that he is not, after all, a Space Ranger, but merely a toy, also has echoes of adult disappointment in accepting reality, and no, I am not just saying this because I completely failed to get a spaceship and zoom through the galaxy taking down evildoers, no matter what my first grade self was not so secretly hoping. It’s presumably not a coincidence that Buzz Lightyear is the creation of people who, like me, grew up on Star Wars and pretending to be Han Solo and Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia and Chewie zipping through the galaxy (our galaxy, not just one far far away). Buzz isn’t just, as Woody admits bitterly, a cool toy: he’s a cool toy that kids can aspire to be.

Other moments also have an adult tinge—most notably the sequence with the Little Green Men (to use their proper name from the later television series), toys which, trapped in one of those claw machines, have developed a full Cult of the Claw. Understandably, since if I have one major plot criticism of this film, it’s that YOU CAN’T ACTUALLY GET A TOY JUST BY LOWERING THE CLAW INTO THE BIN OF TOYS. THERE’S A TRICK (actually several tricks) TO IT. AND THAT’S JUST FOR THE ONES THAT AREN’T RIGGED. Plus, Buzz Lightyear is probably too round to be grabbed by the claw. No wonder the Little Green Men have developed a cult.

Not to mention the moment when Rex the dinosaur explains that he’s not really from Mattel, but “actually from a small company that was purchased in a leveraged buyout,” or the moment when Don Rickles—er, that is, Mr. Potato Head—addresses a walking hockey puck, a joke presumably lost on most of the smaller Toy Story audience members.

If I sound as if I’m saying that Toy Story is more of a film for adults than kids, well, yes, kinda, but kids loved and continue to love Buzz Lightyear; I’ve lost track of the number of children I’ve seen happily clutching Buzz Lightyear toys over the years. For them, I think, Toy Story has two other strengths: it tells kids that although growing up and learning things can be scary, it can also mean adventures and finding new friends. And if you aren’t quite ready to grow up yet—well, you still have your toys. And they love you, very much. As long as you’re kind to them.

As good as Toy Story is, and it is very good, it is light in one respect: girls. The film has only three characters voiced by women, all in minor roles: Woody’s love interest Bo Peep, barely in the film; Andy’s mother, ditto; and Sid’s younger sister Hannah. I won’t harp on this too much, however, since this was addressed in the sequels. Against this, the revelation that the misfit, tortured toys over at Sid’s house aren’t as evil as their appearances would suggest, and are still capable of thinking, fighting, and playing, even if they can no longer talk, is a pretty positive message about the long term effects of disability.

Despite production issues, corporate infighting, and the rather gloomy prognostications of Steve Jobs, who pointed out that the film could at least break even at $75 million, Toy Story outperformed everyone’s wildest expectations by bringing in $373.6 million worldwide. (This number is now known to have increased since through various special and matinee releases, but Disney has not released actual numbers.) If it did not quite break box office numbers for Aladdin and The Lion King, it beat Pocahontas ($346.1 million) to become the number one box office hit for 1995. Steve Jobs’ bet had paid off. Handsomely.

Long term, the tie-in marketing and later franchising proved to be even more lucrative. Toy Story spawned two full length film sequels, Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3, which we’ll be discussing in later posts, with Toy Story 4 currently scheduled for 2019. Toy Story also launched Buzz Lightyear of Star Command, a television series that lasted for two seasons and enjoyed strong DVD sales, as well as a couple of ABC television specials that were later released on DVD/Blu-Ray.

And, of course, toys. Kids adored pretty much all of the toys, particularly Buzz Lightyear, who became an instant bestseller and still continues to fly off shelves at the various Disney Theme Parks. Disney continues to sell multiple tie-in merchandise ranging from the standard clothing and toys to jigsaw puzzles, Disney Trading Pins, light up gloves, cookies, cupcakes, and cell phone cases.

Disney also hastily retooled old dark rides at Magic Kingdom and Disneyland into Buzz Lightyear rides where tourists—er, guests—could shoot at the animatronic figures, something that the theme parks had desperately needed for years. Character Meet and Greets soon appeared at all Disney parks, and Woody and Buzz Lightyear were added to various parades and other attracts.

The other major Toy Story ride was more a spawn of the sequels, but it’s a favorite of mine: Toy Story Midway Mania! at Disney’s Hollywood Studios, a ride that not only lets riders shoot at things, but has the distinction of being one of the most wheelchair AND kid friendly rides I have ever encountered, set up to allow wheelchair users to just board the ride without needing to transfer and to allow small wheelchair users to compete with small siblings and friends. It works well with this film’s scenes of misfit toys who turn out to be, well, just toys, even if honesty compels me to admit that in at least one instance this did lead to certain small park guests throwing things right into the faces of their small siblings, an action greeted with a very stern “WE DO NOT HIT OTHER PEOPLE!” and the response “DARTH VADER DOES” if you want to know where we, as a civilization, stand today.

But Toy Story’s major legacy was not, in the end, any of its sequels, or its successful franchises, or even its theme park rides, but rather, its establishment of Pixar as a major and innovative leader in the animation industry, a company that—finally—looked as if it might just turn a profit.

Originally published in January 2017.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.